Leipzig: How One City Tore Down the Iron Curtain

By Rick Steves

Once trapped in communist East Germany, bustling Leipzig is now a city of business and of culture. It's also a city of great history — Martin Luther, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Johann Sebastian Bach, Felix Mendelssohn, Richard Wagner, Angela Merkel, and many other German VIPs have spent time here.

There are many reasons for visitors to spend time here, too. Music lovers can make a pilgrimage to St. Thomas Church — where Bach was a choirmaster — and to the excellent museum dedicated to him. Art lovers will enjoy the Museum of Fine Arts, history buffs can trek to a Napoleonic battle site at the edge of town, and those turned on by hip hangouts can flock to the "Karli" district just south of downtown.

But there's another compelling reason to visit. The people of Leipzig were at the forefront of the so-called "Peaceful Revolution" that toppled the postwar Communist government. The famous scenes of Berliners joyfully partying atop the Wall were made possible by lesser-known protests that began in Leipzig in 1982. These eventually came to a head in a series of civil-disobedience actions that caught the regime completely off guard in 1989. Expecting an armed insurrection, the Communist leaders were so flummoxed by the peaceful tone of the protests that they simply allowed them to continue.

The epicenter of these events was St. Nicholas Church — Leipzig's oldest (1165) — located in the compact downtown core called Mitte. In the 1980s, prayer meetings held here gradually became the forum for those deeply dissatisfied with communism. As anticommunist sentiment grew, the church was a major staging ground for the Peaceful Revolution. During these protests, people would bravely go inside the church to meet — not knowing what would happen to them when they came back out. To mark those protests, there's now a monumental column outside that echoes the church's Neoclassical interior. Near that column, multicolored panels in the pavement light up after dark, symbolizing the varying opinions about communism.

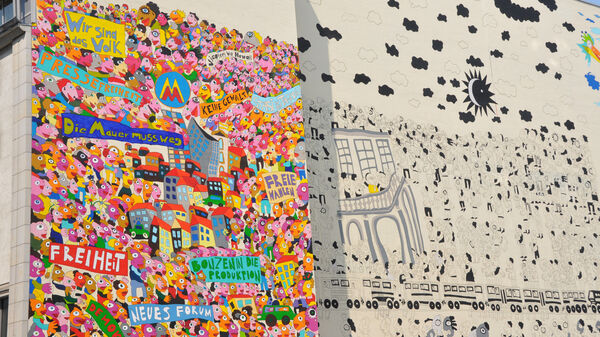

On the streets of the Mitte district, you'll see colorful murals commemorating these anti-communist events. The city center also has two museums that document life behind the Iron Curtain. One is the Stasi Museum in the "Runde Ecke" — the notorious so-called "Round Corner" building — where the East German secret police (Stasi) detained and interrogated those suspected of being traitors. That same building now houses an intriguing exhibit about those harrowing times. A citizens' committee created the museum in 1990 as a temporary exhibit to document Stasi atrocities, with the goal of preventing such things from happening again. Decades later, the museum and its committee are still going strong.

The other East Germany museum — the Contemporary History Forum — is funded by the German government. This center examines life in a divided Germany (1945–1990), focusing mainly on the East but dipping into the West to provide contrast. The exhibit is modern and well-presented, but a helpful audioguide gives it more meaning.

While these museums tend to gloss over it, there's still a surprising gap between the psyches of the East and West. My guide to Leipzig was a Western German now living in the East. One night we sat down to dinner with his wife, who grew up in the communist "DDR" (the initials for the official name of the East German state).

My guide said that only about 1 percent of Germans are in "mixed marriages" between Easterners and Westerners. And more than 20 years after reunification, half of all Western Germans still had never been to the East. His wife added, "Psychologically, people don't want to confront their prejudices."

We talked about the people of Leipzig rising up against the Communists. The government knew that the security forces were likely to sympathize with the people. It was standard operating procedure that border guards and police would work in pairs. That way, if one officer lost his nerve and didn't shoot, the other would — or report the one who didn't.

I remarked how courageous protesters must have been to gather in solidarity inside St. Nicholas Church, not knowing how the soldiers and police would respond when they went outside. My guide's wife, who had participated in the quiet rebellion, spoke of leaving the church cupping candles to let the soldiers know they were unarmed. She said people brought their babies and held them in their arms as human shields. Her husband did a double take — he'd never heard her admit to that before.

Located on the way between the former East Germany (Berlin and Dresden) and the former West (Frankfurt and Nürnberg), Leipzig is a bridge between those two worlds. It may lack half-timbered and lederhosen charm, but Leipzig's fascinating history earns it a place on your European bucket list.