Finding the Quirkier Side of the Cotswolds

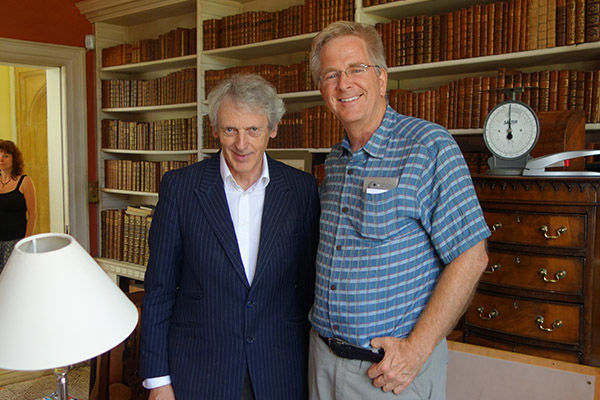

By Rick Steves

While it's a temptation for a travel writer to overuse the word "quaint," I save it for Britain's Cotswolds, a gentle, hilly region two hours northwest of London. By "quaint," I don't mean just thatched cottages and charming teahouses. There's a quirkiness here, too — a time-passed, impoverished-nobility, clueless-aristocracy, provincial-naivety of the region — that charms me to no end. For example, I love how chatty locals, while ever so polite, commonly rescue themselves from a gossipy tangent by saying, "It's all so very…ummm…yaaa."

The Cotswolds are crisscrossed with hedgerows, dotted with storybook villages, and sprinkled with sheep. Made rich by the wool trade, then mothballed by a crash in that same industry, the Cotswolds today is newly prosperous for its popularity with tourists.

Famous towns such as Stow-on-the-Wold, Bourton-on-the-Water, and Chipping Campden are on most tourists' lists, and for good reason. But a short stop in one or two less-touristed corners lets you peek behind the curtain of cuteness. Northleach, south of Stow-on-the-Wold, is my favorite of the Cotswolds' relatively untouched villages. Officials made sure the main road didn't pass through town back in the 1980s, and today it's practically invisible to mass tourism...and I like it that way.

While the town's impressive main square and church attest to its position as a major wool center in the Middle Ages, Northleach mostly consists of a main street leading to a fine old square facing a glorious church.

A bit to the north, the tiny villages of Stanway, Stanton, and Snowshill are as sweet as marshmallows in hot chocolate, nestling side by side just west of the main Cotswolds hubs — and each comes spiced with eccentric characters and odd bits of history.

Stanway, while not much of a village, is notable for its venerable manor house. The Earl of Wemyss, whose family tree charts relatives back to 1202, occasionally opens his melancholy home to visitors. It feels like a time warp — musty and threadbare — even though the earl still lives here with his wife.

The manor dogs have their own cutely painted "family tree," but the Earl of Wemyss admits that his last dog, C.J., was "all character and no breeding." In the great hall, when I marveled at the 1780 Chippendale exercise chair, the earl surprised me. Jumping up onto the tall leather-encased spring, and with the help of the high armrests, he began bouncing. A bit out of breath, he explained, "In grandmama's time, half an hour of bouncing on this was considered good for the liver."

The earl's house has a story to tell. And so do the docents stationed in each room — modern-day peasants who, even without family trees, probably have relatives in this village going back just as far as their earl's. If you probe cleverly, talking to these people gives a rare insight into a quirky slice of England.

The sister villages of Stanway and Stanton are separated by a great oak forest and grazing land with parallel waves actually echoing the furrows plowed by medieval farmers. It's my selfish tradition here to let someone else drive so I can hang out the window, enjoying a windy flurry of stone walls and sheep all under a canopy of ancient oaks.

In Stanton, it seems flowers trumpet, door knockers shine, and slate shingles clap. It's as if a rooting section is cheering me up the town's main street. The church, which dates back to the ninth century, however, betrays a pagan past. Stanton is at the intersection of two lines (called ley lines, which some new-age types consider a source of special power) connecting prehistoric sights. Many churches such as Stanton's were built on pagan holy ground and are generally dedicated to St. Michael — the Christian antidote to pagan mischief. Michael's well-worn figure, looking down at me from above the door, seems to say, "It's all clear now — good Christians may enter." Inside, carved into the capitals in the nave, are pagan symbols for the moon and the sun. But it's "son" worship that's long established here, and the list of rectors goes back to 1269. Sitting in the back pew, fingering grooves worn by sheepdog leashes into the wooden posts, I'm reminded that it was wool money that built this church (at a time when a man's sheepdog accompanied him everywhere).

Snowshill, another nearly edible little bundle of cuteness, has a photogenic triangular square. On one corner stands Snowshill Manor. This dark, mysterious old palace is filled with the lifetime collection of the long-gone Charles Paget Wade. It is one big musty celebration of craftsmanship, from finely carved spinning wheels to frightening samurai armor to tiny elaborate figurines carved by long-forgotten prisoners from the bones of meat served at dinner. Taking seriously his family motto, "Let Nothing Perish," Wade dedicated his life and fortune to preserving things finely crafted. The house (whose management made me promise not to promote it as an eccentric collector's pile of curiosities) really shows off Mr. Wade's ability to recognize and acquire fine examples of craftsmanship. It's all so very…mmm…yaaa.