Bombast & the Axis of Evil

Being here in Iran—part of what George W. Bush once called the "Axis of Evil," in a land whose own president leads chants of "Death to America"—has me thinking about bombast and history.

The word "axis" conjures up images of the alliance of Hitler, Mussolini, and Hirohito that our fathers and grandfathers fought in World War II. People in these countries now believe that each of these leaders maintained his power only because of his ability to stir the simplistic side of his electorate with bombast.

Today, bombast still hogs the headlines, skewing understanding between the mainstream of each country. Most Americans know the Iranian president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, mostly for his provocative statements calling for Israel to be "wiped off the map," as well as denying the existence both of the Holocaust and of gay people in his own country. These are obviously outrageous claims that were, I imagine, intended to shore up his political base. But, much as we might viscerally disagree with Ahmadinejad, it's dangerous to simply dismiss him as a madman. To him, and to his followers, his logic makes sense: if Germany killed the Jews, why are Palestinians (rather than Germans) being displaced to house the survivors? Even as Ahmadinejad rails against Israel, his unwavering policy is that when the Palestinian National Authority accepts the existence of Israel, Iran will, too.

Meanwhile, Iranians get just as fired up about the rhetoric of American politicians. During my visit, Iranians have been buzzing about the potential presidencies of John McCain (who jokingly rewrote the lyrics of the Beach Boys classic song, "Barbara Ann," to become "bomb bomb bomb, bomb bomb Iran") or Hillary Clinton (who said she would "obliterate" Iran if it attacked Israel). For Iranians, hearing the world's lone superpower talk this way is terrifying.

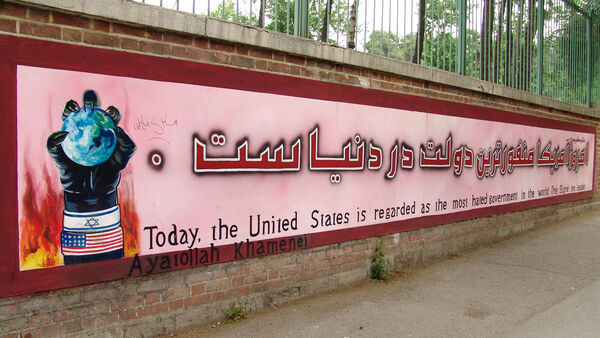

But does that justify the hateful images and slogans I can't avoid as I explore this country? Like our children start each school day pledging "allegiance to one nation, under God," Iranian kids chant angry slogans against the "Great Satan" and its "51st state," Israel. Rather than marketing products to consume, billboards sell an ideology. Some are uplifting (Shia scripture reminding people there is wisdom in compassion). Many others glorify heroes who died as martyrs, taunt the US, cheer for Hezbollah, trumpet "Death to America" and "Death to Israel," and so on. These murals mix fear, religion, patriotism, and a heritage of dealing with foreign intervention.

In our hotel last night, I saw a short documentary about the Palestinians on the Al-Jazeera news network. Coming from a fiercely pro-Israel country, I have my own opinions about this issue. But the Islamic "spin" made it possible for me to grasp the other side's argument; even without understanding the language, the images spoke powerfully. They showed a towering, American-funded wall being built today in the Palestinian territories, concrete block by concrete block...literally blacking out the sunshine from Palestinian communities and making them look and feel like corralled animals. It occurred to me that anyone watching this with empathy for Palestinians (i.e., the entire Muslim world of more than a billion people) would be charged with angry emotions.

Sure, these things confirm the image of Iran that I've seen back home. The problem is, the more I travel here, the more apparent it becomes that it's not the whole story. I can't reconcile the fear-mongering and hate-filled billboards with the huge smiles and welcomes we've received here. People greet me with a smile. Invariably, they ask where I'm from. I often say, "You tell me." They guess and guess, running through six or eight countries before giving up. When I finally tell them, "America," they are momentarily shocked. They seem to be thinking, "I thought Americans hate us. Why would one be here like this?" The smile leaves their face. Then a bigger smile comes back as they say, "Welcome!" or "I love America!"

In a hundred such interactions in our 12 days in Iran, never once has my saying "I am an American" resulted in anything less than a smile or a kind of "Ohhh, you are rich and strong," or "People and people together no problem, but I don't like Bush." (It's clear to me that Iranians like our president as much as Americans like Iran's.)

It's ironic that in most countries these days, Americans find they're better off keeping a low profile. But here, in a country I'm told hates me, my nationality has been a real plus absolutely everywhere I've gone.

President Ahmadinejad has a kind of Hugo Chavez notoriety around the West for his wild and provocative statements. He is an ideologue. His ideas make sense to him, as does his bombast. But everyone in Iran understands—better, perhaps, than we foreigners—that Ahmadinejad is more extreme than the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. And, crucially, the Supreme Leader is more powerful than the president.

Ask anyone who has lived in a country where they disagree with the leaders: Attention-grabbing bombast does not necessarily reflect the feelings (or at least the intensity of feelings) of the man or woman on the street.

Throughout my visit I kept thinking: politicians come and go. The people are here to stay.