Iran Travel Journal (part 5)

Persepolis: This Land Was Once a Superpower

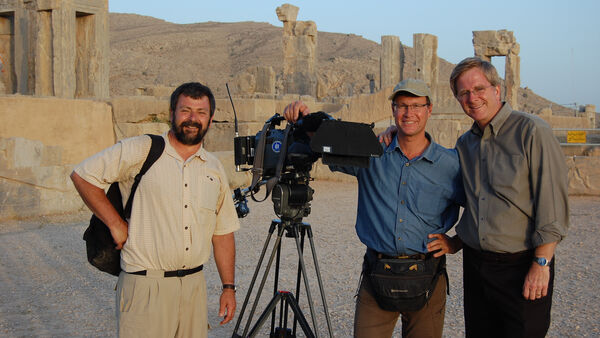

The sightseeing highlight of our time in Iran had to be Persepolis. Persepolis was the dazzling capital of the Persian Empire, back when it reached from Greece to India. Built by Darius and his son Xerxes the Great around 500 BC, this sprawling complex of royal palaces was the awe-inspiring home of the "King of Kings" for nearly two hundred years. At the time, Persia was so mighty, no fortifications were needed. Still 10,000 guards served at the pleasure of the emperor. Persepolis, which evokes the majesty of Giza or Luxor in Egypt, is (in my opinion) the greatest ancient site between the Holy Land and India.

Bottom: About 2,500 years ago, subjects of the empire (from 28 nations) would pass through the Nations' Gate, bearing gifts for the "King of Kings."

My main regret from traveling through Iran on my first visit (back in 1978) was not trekking south to Persepolis. And I wanted to include Persepolis in our TV show because it's a powerful reminder that the soul of Iran is Persia, which predates the introduction of Islam by a thousand years. Arriving at Persepolis, in the middle of a vast and arid plain, was thrilling. This is one of those rare places that comes with high expectations and actually exceeds them.

We got here after a long day of driving — just in time for that magic hour before the sun set. The light was glorious, the stones glowed rosy, and all the visitors seemed to be enjoying a special "sightseeing high." I saw more Western tourists visiting Persepolis than at any other single sight in the country. But I was struck most by the Iranian people who travel here to savor this reminder that their nation was a huge and mighty empire 2,500 years ago.

Wandering the site, you feel the omnipotence of the Persian Empire, and get a strong appreciation for the enduring strength of this culture and its people. I imagined this place at its zenith: the grand ceremonial headquarters of the Persian Empire. Immense royal tombs, reminiscent of those built for Egyptian pharaohs, are cut into the adjacent mountainside. The tombs of Darius and Xerxes come with huge carved reliefs of ferocious lions. Even today — 2,500 years after their deaths — they're reminding us of their great power. But, as history has taught us, no empire lasts forever. In 333 BC, Persepolis was sacked and burned by Alexander the Great, replacing Persian dominance with Greek culture...and Persepolis has been a ruin ever since.

The approach to this awe-inspiring sight is marred by a vast and ugly tarmac with 1970s-era light poles. Reminiscent of another megalomaniac ruler, this hodgepodge is left from the Shah's 1971 party celebrating the 2,500-year anniversary of the Persian Empire — designed to remind the world that he ruled Persia with the extravagance of a modern-day Xerxes or Darius. The Shah flew in dignitaries from all over the world, along with dinner from Maxim's in Paris, one of the finest restaurants in Europe. Iranian historians consider this arrogant display of imperial wealth and Western decadence the beginning of the end for the Shah. Within a decade, he was gone and Khomeini was in. It's my hunch that the ugly asphalt remains of the Shah's party are left here so visiting locals can remember who their Revolution overthrew.

As in any desert, the temperature dropped dramatically after the sun set. I pressed my body against the massive stone walls to feel the warmth stored in the stones. The next morning, under a blistering sun, I hugged the same wall to catch the cool of the night that it still carried.

Martyrs’ Cemetery: Countless Deaths for God and Country

War cemeteries always seem to come with a healthy dose of God — as if dying for God and country makes a soldier's death more meaningful than just dying for country. That is certainly true at Iran's many martyr cemeteries.

Most estimates are that there were over a million casualties in the Iran-Iraq War. Iran considers anyone who dies defending the country to be a hero and a martyr. Each Iranian city has a vast martyrs' cemetery from this conflict. Tombs seem to go on forever, and each one has a portrait of the martyr and flies a green, white, and red Iranian flag. All the dates are from 1980 to 1989. Over two decades later, the cemetery is still very much alive with mourning loved ones. While the United States lives with the scars of Vietnam, the same generation of Iranians live with the scars of their war with Iraq — a war in which they, with one-quarter our population, suffered three times the deaths.

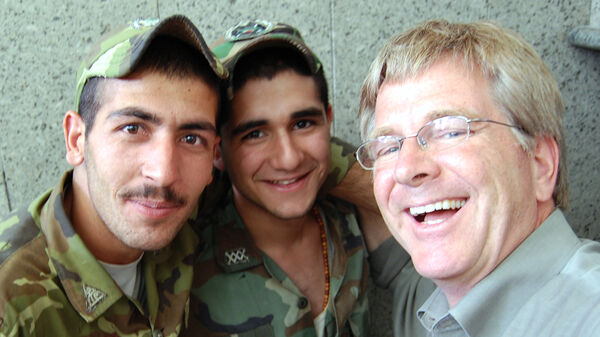

A steady wind blows through seas of flags on the day of our visit, which adds a stirring quality to the scene. And the place is bustling with people — all mourning their lost loved ones as if the loss happened a year ago rather than twenty. The cemetery has a quiet dignity, and — while I feel a bit awkward at first (being part of an American crew with a big TV camera) — people either ignore us or make us feel welcome.

We meet two families sharing a dinner on one tomb (a local tradition). One of the fathers insists we join them for a little food. They tell us their story: They met each other twenty years ago while visiting their sons, who were buried side by side. They became friends, their surviving children married each other, and ever since then they gather regularly to share a meal on the tombs of their sons.

A few yards away, a long row of white tombs stretches into the distance, with only one figure interrupting the visual rhythm created by the receding tombs. It's a mother cloaked in black sitting on her son's tomb, praying — a pyramid of maternal sorrow.

Nearby is a different area: marble slabs without upright stones, flags, or photos. This zone has the greatest concentration of mothers. My friend explains that these slabs mark bodies of unidentified heroes. Mothers whose sons were never found come here to mourn.

I leave the cemetery sorting through a jumble of thoughts:

How oceans of blood were shed by both sides in the Iran-Iraq War — a war of aggression waged by Saddam Hussein and Iraq against Iran.

How invasion is nothing new for this mighty and historic nation. (When I visited the surprisingly humble National Museum of Archaeology in Tehran, the curator explained that the art treasures of his country were scattered in museums everywhere but in Iran.)

How an elderly, aristocratic Iranian woman had crossed the street to look me in the eye and tell me, "We are proud, we are united, and we are strong. When you go home, please tell the truth."

How, with a reckless military action, this society could be set ablaze — the uniquely Persian mix of delightful little shops, university students with lofty career aspirations, gorgeous young adults with groomed eyebrows and perfect nose jobs, hope, progress, hard work, and the gentle people I experienced here in Iran could so easily and quickly be turned into a hell of dysfunctional cities, torn-apart families, wailing mothers, newly empowered clerics, and radicalized people.

My visit to the cemetery drove home a feeling that had been percolating throughout my trip. There are many things that Americans justifiably find outrageous about the Iranian government — from supporting Hezbollah and making threats against Israel; to oppressing women and gay people; to asserting their right to join the world nuclear club.

And yet, no matter how strongly we want to see our beliefs and values prevail in Iran, we must pursue that aim carefully. What if our saber-rattling doesn't coerce this country into compliance? In the past, other powerful nations have underestimated Iran's willingness to be pulverized in a war...and both Iran and their enemies have paid the price.

I have to believe that smart and determined diplomacy can keep the Iranians — and us — from having to build giant new cemeteries for the next generation's war dead. That doesn't mean "giving in" to Iran…it means acknowledging that war is a failure and it behooves us to find an alternative.